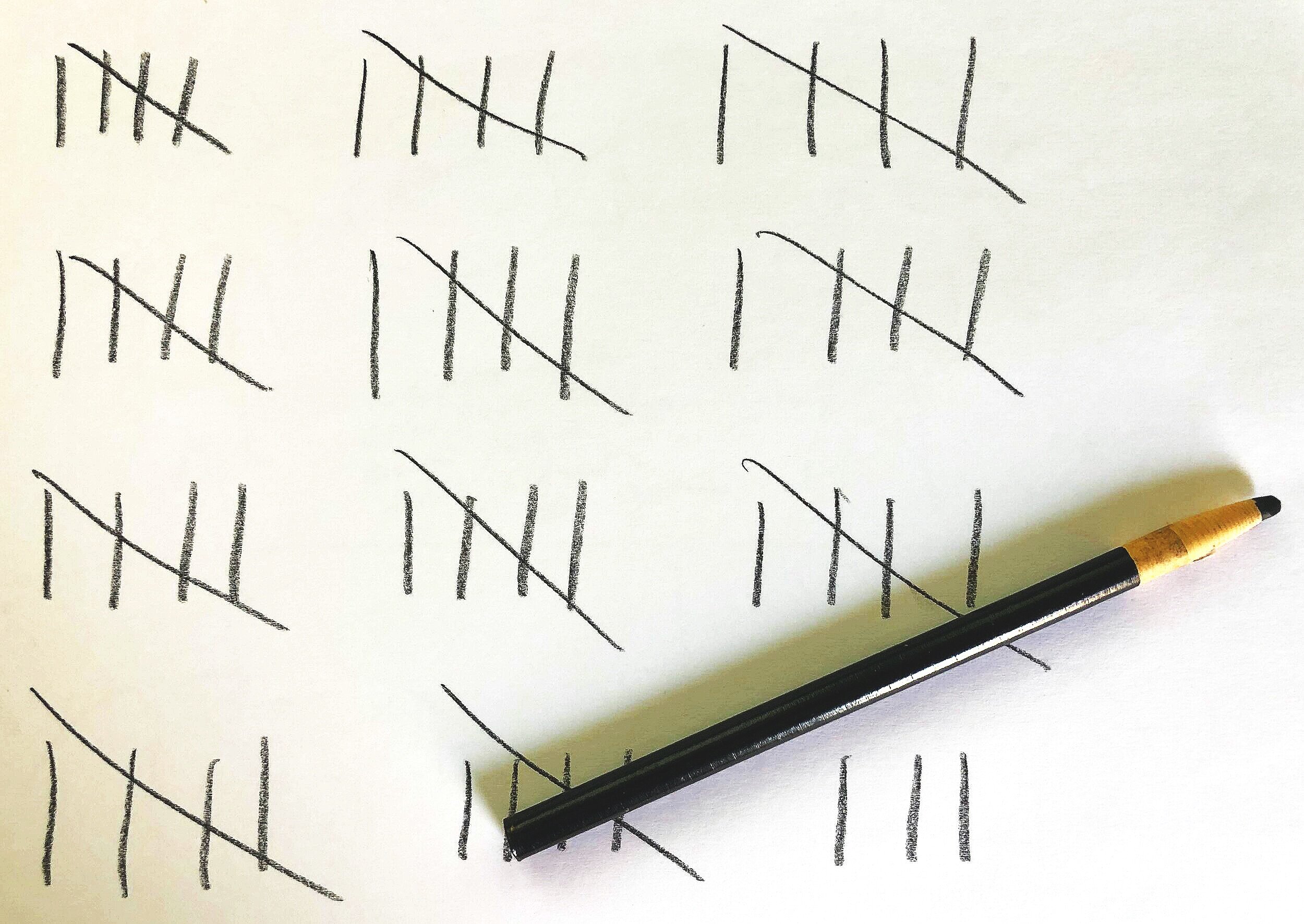

Big data means something else entirely if you don’t want to lose track of your count.

To be effective, stories must trade in specificity. Stories need to let us know how things feel, how they taste, what they look like, how they smell. The moments we remember are often the sensual ones. Certainly there are intellectual discoveries that can shock us to new levels of consciousness like Frankenstein's monster being hit by lightning. But most of the stuff that captures our attention and our imaginations resonate when we feel them. As John Keats put it, “…axioms in philosophy are not axioms until they are proved upon our pulses.” It’s arguable that even the brainy thrill that comes from suddenly discovering a profound scientific or mathematical insight is, in itself, made memorable by the quickening of one’s pulse. The insight into a technical truth makes itself real to us by the feel of our beating hearts and quickened breath.

This, however, is an era defined by data. Rather than walk lazily through a riparian meadow, you’re more likely going to just Google some pix. It’s less work, faster, and your fridge is nearby. Click “images”: instant meadow.

But perhaps you’re feeling expansive. If, perchance, you’re actually standing in the middle of a sun-kissed glade, the long shadow cast by the ubiquitous Cloud likely extends over you anyway. You’ll probably reach for your ever-present battery powered appendage and post a picture to the platform of your choice, chockablock with meta-tags. Suddenly your own day in the meadow becomes yet another database byte in the field of pixelated mountain flowers. You’ve fed the big data maw with one more, and in so doing, you pulled yourself out of the actual experience for a moment and back into the flat glass of your phone.

Shall I compare these to a summer’s day? Depends on whether there’s good cell signal, apparently.

But who am I kiddin’? This ain’t no polemic! I love my tech as much as you do. It’s true, it’s true: I’m a geek through and through. The issue here is that the lure of big data can impede on experience and sensation. Big data asks us to add, to add, to add. Big data doesn’t ask us to discern. If you’re standing in a meadow, rays of sun illuminating blossoms and birds alike, you might consider fully immersing yourself in that singular moment rather than millions of others like it. This moment is your own. The bottomless well of data asking you to tithe one more digital bit cares not a whit for what you see, what you smell, what you feel when the rising afternoon breeze kisses your skin.

The Luddites effectively proved their own flaws, even as they simultaneously made important philosophical points by rejecting modern solutions to preserve anachronistic jobs. I understand the power of big data. Some insights are simply invisible without it. Try to describe the apparent chaos of high-velocity atmospheric winds and you’re immediately lost like a stringless kite. See those winds visualized by mathematically precise vector fields, and the breathing Earth suddenly appears. The problem here is not the data itself. The problem is not in deep understanding either, even if that may take some work to achieve. The problem is the growing belief that data itself is the singular highway to deep truth. More data doesn’t make something more meaningful. This is not an either/or proposition. Some data yields its secrets because its deeper meaning only emerges when placed into a gigantic context. Big data can offer insights by showing patterns or trends that require thousands of measurements for them to appear, patterns that would be otherwise invisible in anything smaller than a massive tranche.

In stories, we don’t necessarily need to hear “more”. We need to hear what matters. There’s always more story that could be told. There’s always more paint that could be applied. There’s always a wider lens or a busier stage or more complex notes that could be played. Artistic quality may be a topic of timeless debate, but one thing is clear. Artistic quality comes by making choices, some invested in limitations as much as from expansive inclusions. Where Neal Stephenson presents hundreds of expository pages to create the space for his stories, he still selects which aspects to include. Nicholson Baker, conversely, tells his stories in miniature, but his precise selections define the cosmos of his creations.

This is to say, “I’m listening.”

Tell the story again about how it felt that afternoon when you went skinny dipping in the lake.

Breathe slowly and whisper about the day the soldiers came dragged your townsfolk away.

Remind me how you lost all sense of time when the doctor placed your new baby daughter in your hands, sixty second old.

More data doesn’t make these stories better. Big data will not improve a great first date, even if you swiped right one night looking for Mister Right.

Choices make life real. Data simply describes reality. The problem with big data is that it urges us to believe it’s the best way to arrive at optimized quality, solutions that stand the test of analysis and repeatability. Sure, there’s value in big data. There’s a ton. But some of the best moments in life writ big and small happened without regard to direct measurement, and with life as fleeting and fragile as it is, I would hate to miss the chance to experience any one of them simply because the statistical trend line tell me where things are headed.